In 2022, cycle of systematic violation and attacks on rights reflected in increased violence against Indigenous Peoples

Cimi’s annual Report exposes the violence against Indigenous Peoples and presents an overview of Bolsonaro’s term in office, defined by violations and the dismantlement of the stances of protection and assistance

The year 2022 marked the end of a governmental cycle marked by violations and an increase in violence against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil. As it has been throughout the last three years, the conflicts and the invasions to Indigenous territories advanced, and so did the dismantlement of Public Policies geared toward Native Peoples, such as health care and education, and of the institutions responsible for the protection of their territories. Such is the reality presented in this Report Violence against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil – data from 2022, an annual publication by the Indigenous Missionary Council (Cimi).

Events that caused overspread national and international commotion made evident the dire situation in Brazil, such as the homicides of Bruno Pereira and the British journalist Dom Phillips, killed in June at the Indigenous Land Vale do Javari, in Amazonas state, by invaders of the territory; or the illegal gold mining on Yanomami lands which, neglected by the government, led to an unprecedented humanitarian crisis in the area.

In regards to the health care of the Indigenous Peoples, alongside shocking images and accounts that circled during the year, the data gathered in this Report shows alarming numbers of child mortality, murders and territorial violations. In those categories, the states of Roraima and Amazonas, where the Yanomami Land is located, were among those which registered the higher numbers.

2022 was also the year that ended a four-year cycle during which no new Indigenous Land was demarcated by the Federal Government. Under Bolsonaro, the Executive not only ignored its constitutional obligation to demarcate and protect Indigenous Lands but acted directly to undermine the rights of Indigenous Peoples to their territories, through Projects of Laws and administrative measures that aimed on opening those territories for exploitation.

The intensity of the attacks cannot be understood outside of the frame of the dismantling of the indigenist policies and environmental protection institutions that the government had been committed to during the term of Jair Bolsonaro

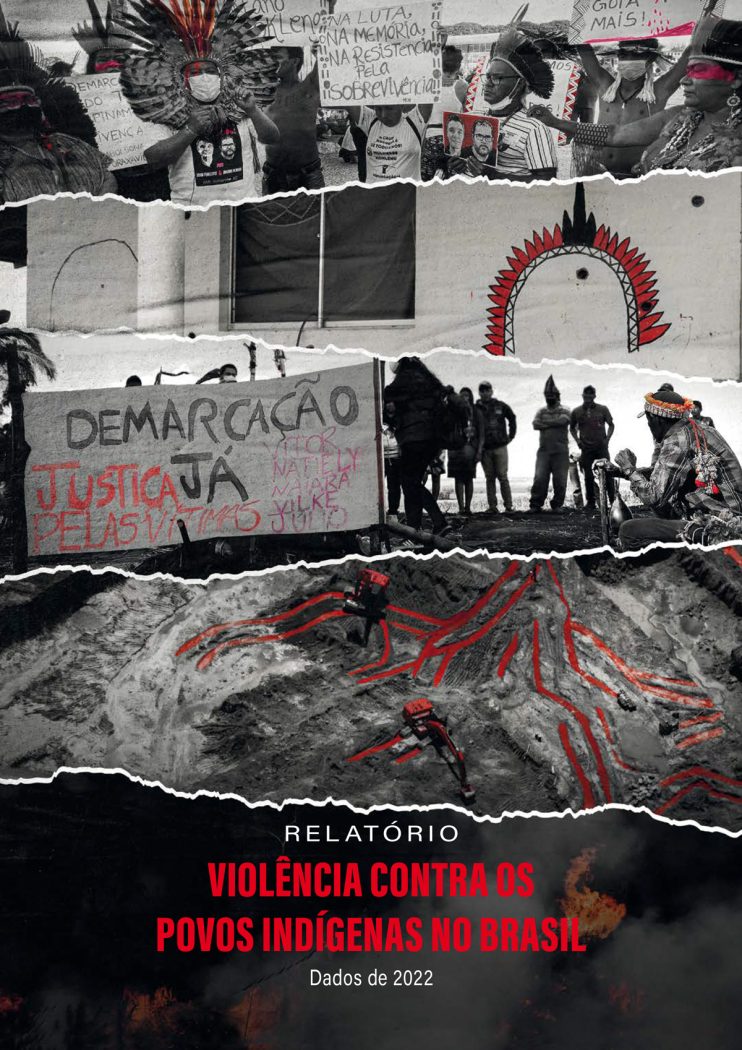

Indigenous demonstration against the Project of Law proposed by Bolsonaro government to legalize mining in Indigenous Lands. Free Land Camp, Brasília, capital of Brazil, 2022. Foto: Hellen Loures/Cimi

Besides Bolsonaro’s speeches, a recurrent stance was registered in institutions like the Federal Attorney General (AGU), and even the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai). The positioning of those state agencies in judicial and administrative processes was nearly every time against Indigenous Peoples’ rights and favourable to the economic agenda of agrobusiness and the mining sector.

Such a stance reflects now in a high register of cases involving territorial conflicts, peaking at 158, and property invasion, with a total of 309 cases in 218 Indigenous lands, throughout 25 states.

In many states, like Mato Grosso do Sul, Maranhão e Bahia, the conflicts and the total lack of state protection of Indigenous Peoples resulted in record numbers of assassinations, sometimes involving police forces operating as ‘private security’ of big farmers. In Comexatibá Indigenous Land, in southern Bahia, 14 years old Pataxó boy Gustavo Silva da Conceição was brutally killed during one of several shootings perpetrated by Militias.

At the Taquaperi Indigenous Reserve, in the municipality of Coronel Sapucaia, state of Mato Grosso do Sul, the killing of 18-year-old Guarani Kaiowá Alex Recarte Lopes motivated a series of land territorial repossessions by the natives that were harshly attacked by farmers and warrantless police operations.

One such operation, which took place at Tekoha Guapoy, municipality of Amambai, resulted in the death of 42-year-old Guarani Kaiowá man Vitor Fernandes and injured many others. So vicious was the attack, that the Kaiowá and Guarani people started referring to it as the ‘Guapoy Massacre’.

Of course, the intensity of the attacks cannot be understood outside of the frame of the dismantling of the indigenist policies and environmental protection institutions that the government had been committed to during the term of Jair Bolsonaro. For this reason, this year’s Report presents also an overview of the whole period and an update on the data that reveal this reality.

So, the Report of 2022 analyses also the data on killings, suicides and infant mortality of the last four years. Data was gathered from public sources like the Special Secretariat of Indigenous Health (Sesai), the Information System on Mortality (SIM), and state-level Health Secretariates.

The intentional and openly neglectful stance of Bolsonaro’s Government on the demarcation of Indigenous Lands resulted in a deepening effect on territorial rights-related conflicts, frequently leading to death threats, armed assaults and assassinations of Indigenous leaders

Devastação causada pelo garimpo na TI Yanomami. Registro feito em dezembro de 2022, durante sobrevoo realizado pelo Greenpeace. Foto: Valentina Ricardo

Violence against Heritage

Violence cases against the heritage of Indigenous Peoples are presented in the first chapter of this Report and are divided into three categories: omission and delay in land regularisation, with 867 cases registered; territorial rights-related conflicts, 158 cases; and illegal exploitation of natural resources and miscellaneous damage to property, a category that is in its seventh consecutive year of growth, with 309 cases.

In total, 2022 had 1.334 cases of violence against the heritage of Indigenous Peoples. Among the main types of damage to Indigenous heritage, stands out the exploitation of natural resources such as illegal woodlogging, mining, game and fishing, and possessory invasions.

The majority of the 1.391 recorded Indigenous lands and territorial demands existent in Brazil (62%) remain pending some kind of administrative action for demarcation, points out the survey made by Cimi, updated every year. Of the 867 indigenous lands with pending issues, at least 588 have had no Governmental action on their demarcation and wait still for the development of Technical Groups (GTs) by Funai in order to proceed with the identification and delimitation of those areas.

On the same note, the few Technical Groups created or re-established in 2022 were only constituted by actions moved by the Federal Public Ministry (MPF), and none have completed their work.

The intentional and openly neglectful stance of Bolsonaro’s Government on the demarcation of Indigenous Lands resulted in a deepening effect on territorial rights-related conflicts, frequently leading to death threats, armed assaults and assassinations of Indigenous leaders.

Enterro do Guarani Kaiowá Vitor Fernandes, morto no “massacre do Guapoy”. Foto: povo Guarani e Kaiowá

Violence against the person

The second chapter gathers the acts of violence against individuals. In this section, the following cases were registered: abuse of power (29); death threats (27); other threats (60); assassinations (180); wrongful deaths (17); aggravated assaults (17); ethnic-cultural racism and discrimination (38); attempted murder (28); and sexual violence (20).

Therefore, the accounts totalize 416 cases of violence against indigenous individuals in 2022. Taken as a whole, the four-year term under Bolsonaro has an average of 373,8 cases per year. For reference, the four years of the government of Dilma Rousseff and Michel Temer had an average of 242,5 annual cases.

As it was in the last three years before, in 2022 the states that registered the highest quantity of assassinations of indigenous people were Roraima (41), Mato Grosso do Sul (38) and Amazonas (30). Those three states gathered almost two-thirds (65%) of all of the 795 homicides of Indigenous Peoples between 2019 and 2022: 208 in Roraima, 163 in Amazonas and 146 in Mato Grosso do Sul.

Among those, some cases stand out like the assassination of Guarani and Kaiwoá leaders Marcio Moreira and Vitorino Sanches, in the following months of the ‘Guapoy Massacre’, in which the young Vitor Fernandes was killed. Also, the September killings of three Guajajara men from Arariboia Indigenous Land – Janildo Oliveira, Jael Carlos Miranda and Antônio Cafeteiro.

Threats and attempted assassinations were also registered in high numbers. This kind of aggression was mostly perpetrated by big farmers, illegal miners, loggers, fishermen and hunters.

Elevated numbers of abuse of power were a constant throughout the four years under Bolsonao: a total of 89 cases making an average of 22,2 cases per year. That is twice as high that the four precedent years under Rousseff and Temer, with an average of 8,7 per year. All of those categories reflect directly the widespread institutional degradation and dismantling of the state protection of the Native Peoples during the period.

Part of the healthcare structures in Yanomami Land was appropriated by the illegal mining operations, in isolated regions, meaning the reality is probably worse than the data

Acampamento Terra Livre 2022. Foto: Hellen Loures/Cimi

Violence by Omission of the State

The cases of Violence by omission of the State are organized in the third chapter of the Report in seven categories. Through the Brazilian Law of Access to Information (LAI), Cimi obtained partial information about the mortality of indigenous children aged 0 to 4 years. Data supplied by the responsible organ of the government reveal the occurrence of 835 indigenous child deaths in 2022. The majority were registered in the states of Amazonas (233), Roraima (128), and Mato Grosso (133).

In the whole country, Sesai registered a total of 3.552 deaths between 2019 and 2022 in the age range. Considering four years, the same states concentrated the majority of the deaths. In total, 1.014 children under the age of 5 died in the state of Amazonas, 607 in Roraimia, and 487 in Mato Grosso, according to the same data.

The Indigenous Sanitary District (DSEI) Yanomami e Ye’kwana, which covers the Yanomami Lands between the states of Amazonas and Roraima, registered alone 621 child deaths aged 0 to 4 years between 2019 and 2022. 17,5% of all deaths in this age range. According to DSEI, the Yanomami population in the demarcated lands is estimated at approximately 30,5 thousand people. Still, part of the healthcare structures was appropriated by the illegal mining operations, in isolated regions, meaning the reality is probably worse than the data.

Information from official sources, gathered from regional health care units, indicate the occurrence of 115 suicide amongst indigenous peoples in 2022. The majority happened in the states of Amazonas (44), Mato Grosso do Sul (28) and Roraima (15). Over a third of the deaths by suicide are from people up to 19 years old.

In the period between 2019 and 2022, updated data from the same sources show 535 deaths by suicide among indigenous peoples. Again, Amazonas (208), Mato Grosso do Sul (131), and Roraima (57), are the states in which the majority of the cases took place: 74% of the total for the four years.

Also in the chapter are presented the registered cases of general lack of assistance (72 cases); lack of assistance in education (39); lack of assistance in health care (87); dissemination of alcohol and other drugs (5); and death by lack of health care (40); in an overall total of 243 cases.

Even among those recognized by the government, many isolated groups were completely unprotected during 2022

Manifestação de indígenas da TI Vale do Javari em Atalaia do Norte (AM), em junho, cobrando proteção contra as invasões ao território que possui a maior concentração de povos isolados do mundo. Foto: Antonio Scarpinetti/SEC/Unicamp

Isolated Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous Peoples in voluntary isolation are among the most affected groups by the omission and deliberated lack of protection stance adopted by Bolsonaro’s government. The year 2022 brought about an even worsening scenario. This topic is dealt with in the fourth chapter of the Report.

Invasions and damage to the heritage were registered in at least 36 Indigenous Lands where up to 60 isolated Indigenous Peoples live, according to the data of Support of the Free Peoples Team (Eapil/Cimi). And such a scenario is aggravated since the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai) does not recognize 86 of the 117 groups of isolated Indigenous Peoples registered by Cimi. Those groups are effectively invisible to the State, as is all the violence that they are subject to, including the risk of eminent genocide.

Even among those recognized by the government, many isolated groups were completely unprotected during 2022. That is the case of the Isolated People of Mamoriá Grande, which presence was confirmed by Funai, but no protection measure was adopted to protect them. Also, the Isolated People of Jacareúba/Katawixi, had no protection during 2022 because of the decision of the Agency, under its president Marcelo Xavier, not to renovate the Land’s Restriction Ordinance.

Such Ordinances are measures adopted specifically to the protection of the territories of Indigenous Peoples in voluntary Isolation which are not yet demarcated, as a means to impede invasions in the area. Bolsonaro’s government abstained from renovating the Ordinances or renovating for small periods of six months. This was interpreted as signalling to invaders and landgrabbers that those territories would soon be available for exploitation and private appropriation. Large-scale invasion ensued in Indigenous Lands such as Piripkura, in the state of Mato Grosso; and Ituna/Itatá, in the state of Pará.

These policies were followed by continuous weakening of the Protection Bases (BAPEs) of Funai, responsible for the surveillance of the lands inhabited by isolated Indigenous Peoples. They were left resourceless, completely incapacitated to operate, as was evident in the cases of the Indigenous Lands Vale do Javari and Yanomami.

Manifestação em frente ao Ministério da Justiça, em setembro de 2022, cobrando justiça após uma série de assassinatos de indígenas naquele mês. Foto: Tiago Miotto/Cimi

Memory

The fifth chapter of the Report is dedicated to the subject of Memory and Justice and brings about the last works of researcher Marcelo Zelic (1863-2023), who passed away this current year. Zelic dedicated his life to the preservation of memory through documentation work and the advocacy for the creation of devices for the non-repetition of Human Rights violations against Indigenous Peoples.

In the last years, Zelic worked for the creation of a National Indigenous Commission of Truth (CNIV) for verification and reparation of those violations. In this paper of his, published by Cimi here for the first time, Zelic defends the proposition and delineates his ideas about attributions, operation and structure of the Comissão.

Articles

This current edition of the Report presents reading articles that enhance the understanding of the data and information addressed in the mentioned chapters. There is an analysis of the dire situation of the Yanomami Land and the concept of genocide, historically relating the omission of the State facing the illegal mining, and the occurrent violence against this Indigenous People, with the Haximu massacre of 1993 – the first case ever ruled a crime of genocide in Brazil. Also, two other articles debate the reality of incarcerated indigenous individuals in Brazil and the denial of their rights by the Judicial System; and the dismantlement of the indigenist policies of the State by the government under Bolsonaro’s term, analysed through the study of the usage of funds and budget by the State.

The Report Violence against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil is an annual publication of the Indigenous Missionary Council (Cimi), an organization linked to the National Bishops’ Conference of Brazill (CNBB). Founded in 1972, Cimi has been acting for fifty years in the defence of the Indigenous People’s causes.

Translated from Portuguese by Christian Crevels