In 2019, Indigenous Lands were ostensibly invaded from north to south of Brazil

Cimi’s report shows an alarming increase in violence against Indigenous Peoples in the first year of the Bolsonaro government

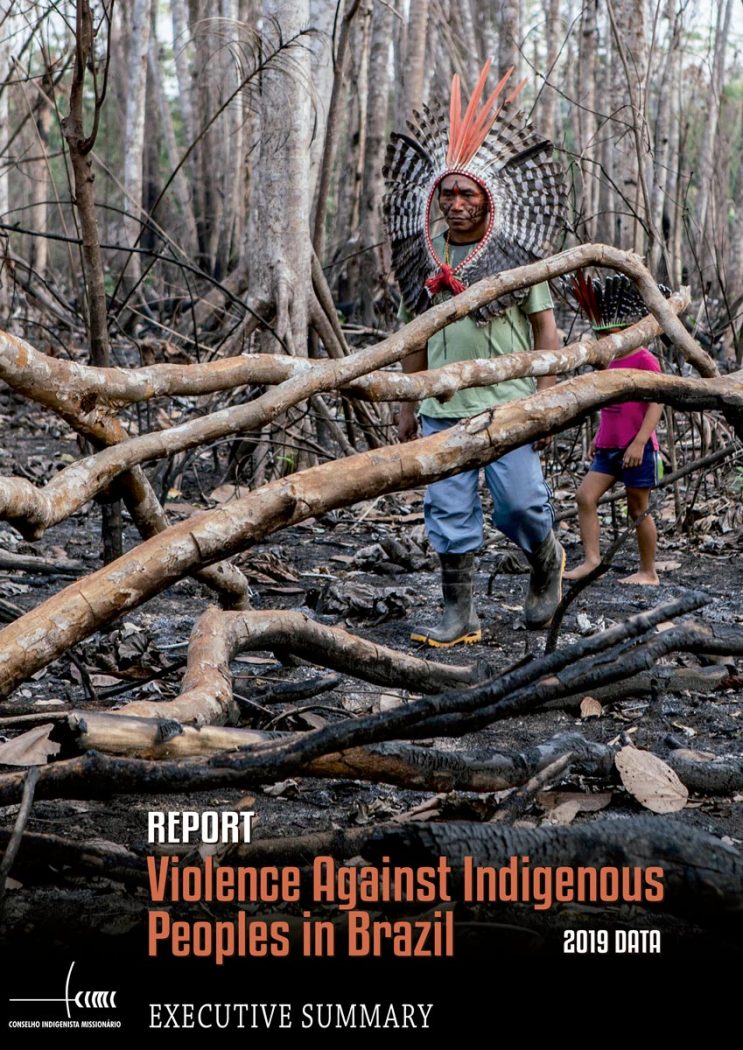

The report Violence Against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil – 2019 data, published annually by the Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples (CIMI for its Portuguese acronym), reiterates the picture of an extremely perverse and worrying reality of the indigenous peoples in Brazil in the first year of Jair Bolsonaro as president of the country. The intensification of expropriations of indigenous lands, forged in the invasion, land grabbing, and subdivision of the lands, is quickly and aggressively being consolidated throughout the national territory, causing immeasurable destruction.

In addition to materializing the recognition of an original right, indigenous lands are evidently the areas that most protect forests and their rich ecosystems. Historically, the presence of indigenous peoples within their territories has made them function as real barriers to the advance of deforestation and other plunder processes. However, 2019 data reveals that the indigenous peoples and their traditional territories are being explicitly usurped.

The “explosion” of criminal fires that devastated the Amazon and the Cerrado in 2019, with vast international repercussions, should be put into this broader perspective of the destruction of indigenous territories. Oftentimes, fires are an essential part of a criminal land-grabbing scheme. The “clearing” of extensive areas of forest is done to enable the implementation of crops, for example. In a nutshell, this chain works like this: invaders deforest, sell the wood, set fire to the forest, start the pasture, fence the area, and, finally, after the “clearing,” place cattle in the area and, later, plant soy or corn.

Unfortunately, the violence against indigenous peoples is based on a government project that aims to make their land and the common assets contained therein available to agribusiness, mining, and logging entrepreneurs, among others.

The report points out that, in 2019, there was an increase in cases in 16 of the 19 categories of violence systematized by the publication. Particular attention is drawn to the intensification of records in the category “possessory invasions, illegal exploitation of resources, and damage to property,” which, from 109 cases registered in 2018, jumped to 256 cases in 2019.

In tune with reality, these data explain an unprecedented tragedy in the country: indigenous lands are being ostensibly invaded and destroyed across the country. In some instances described in the report, the invaders even mentioned the name of President Jair Bolsonaro, showing that their criminal actions are encouraged by those who should fulfill their constitutional obligation to protect indigenous territories, which are the country’s heritage.

It is also unfortunate to note that the increase in cases almost doubled, compared to 2018, in 5 other categories, in addition to “invasions/illegal exploitation/damage.” This can be seen in “territorial conflicts,” which went from 11 to 35 cases in 2019; “death threat,” which went from 8 to 33; “various threats”, which went from 14 to 34 cases; “intentional bodily injuries”, which almost tripled, going from 5 to 13; and “deaths due to lack of assistance,” which went from 11 to 31 cases in 2019.

Property-Related Violence

Concerning the three types of “Property-Related Violence,” which comprise the first chapter of the report, the following data were recorded: omission and delay in land regularization (829 cases); conflicts over territorial rights (35 cases); and possessory invasions, illegal exploitation of natural resources, and various damage to property (256 registered cases); totaling 1,120 cases of violence against the heritage of indigenous peoples in 2019.

It should be noted that of 1,298 indigenous lands in Brazil, 829 (63%) are pending something from the government to finalize its demarcation process and registration as a traditional indigenous territory with Brazil’s Department of National Heritage (Secretaria do Patrimônio da União, SPU). Of these 829, a total of 536 lands (64%) have had zero action from the government.

In addition to fulfilling his promise not to demarcate an inch of indigenous land, President Bolsonaro and his administration, through its Ministry of Justice, returned 27 demarcation processes to the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) in the first half of 2019, to be reviewed. This action certainly implies more significant obstacles, if not the impediment, to the fulfillment of the constitutional rights of the indigenous people who claim their ancestral territories.

Last year alone, there was an increase of 134.9% of cases related to invasions compared to those recorded in 2018

Denisa Sterbova/Cimi

As mentioned, in 2019, 256 cases of “possessory invasions, illegal exploitation of resources, and damage to property” were recorded in at least 151 indigenous lands, of 143 indigenous peoples, in 23 states. Confirming the forecast made by CIMI last September, on the occasion of the launch of its previous report, these data reveal an extremely worrying reality: last year alone, there was an increase of 134.9% of cases related to invasions compared to those recorded in 2018. This represents more than double the 109 cases recorded in 2018.

A more detailed analysis of the descriptive records of each of these 256 cases reveals that in most situations of invasion/exploitation/damage, there was a record of more than one type of damage/conflict, totaling 544 occurrences. Thus, it is possible to see a breakdown of the 256 consolidated cases according to the following motivations:

89 for illegal logging/deforestation;

39 for mining and mineral exploration;

37 for agricultural farms (cattle, soy, and corn);

31 for fires;

31 for predatory fishing;

30 for illegal land grabbing/subdivision;

25 for predatory hunting;

25 for infrastructure projects (highway, railroad, electricity);

14 for illegal exploitation of resources (sand, marble, stone, heart of palm);

7 for contamination of water and/or food by pesticides;

5 for tourism projects;

3 for the drug trafficking route;

It should also be noted that these 256 cases included 107 occurrences of damage to the environment (77) and damage to property (30), denounced by indigenous peoples, in their lands.

The enormous repercussions of the murder of Paulo Paulino Guajajara, following an ambush by invaders, inside the Arariboia Indigenous Land, in Maranhão, in November 2019, exposed, once again, that tension in that state reaches alarming levels

Tiago Miotto/Cimi

Violence Against People

Invariably, the violence against indigenous peoples and their communities is associated with the dispute over land. In the second chapter, “Violence against People,” the following data were recorded in 2019: abuse of power (13); death threat (33); various threats (34); murders (113); manslaughter (20); intentional bodily injuries (13); racism and ethnic-cultural discrimination (16); assassination attempt (25); and sexual violence (10); totaling 277 cases of violence against indigenous peoples in 2019. This total of records is more than double the total recorded in 2018, which was 110.

The total of 113 records of indigenous people murdered in 2019, according to official data from the Special Department for Indigenous Health (Secretaria Especial de Saúde Indígena, SESAI), is slightly lower than the total systematized in 2018, which was 135. The two states with the highest number of murders recorded were Mato Grosso do Sul (40) and Roraima (26). It is important to note that the data provided by SESAI on “deaths resulting from aggressions” do not allow for more in-depth analysis because they do not present information on the age group and people of the victims, nor the circumstances of the murders. They are still subject to review, which means that the number of cases may be worse.

Unfortunately, it appears that in 2019 the indigenous population of Mato Grosso do Sul (2nd largest in the country) continued to be the target of constant and violent attacks, in which there is even a record of torture, including against children.

The enormous national and international repercussions of the murder of Paulo Paulino Guajajara, following an ambush by invaders, inside the Arariboia Indigenous Land, in Maranhão, in November 2019, exposed, once again, that tension in that state reaches alarming levels. Invaded and looted for decades, the traditional territories of Maranhão reflect a reality that spreads and worsens throughout the country.

Overflight records areas of illegal mining within the Munduruku Indigenous Land in Pará in September 2019. Christian Braga/Greenpeace

Violence due to Government Omission

There was an increase in registrations in all categories of this third chapter, with a total of 267 registered cases of “violence due to government omission.”

Based on Brazil’s Access to Information Act, CIMI obtained partial data on indigenous peoples’ suicide and childhood mortality from SESAI. There were 133 suicides recorded across the country in 2019; 32 more than the cases registered in 2018. The states of Amazonas (59) and Mato Grosso do Sul (34) registered the highest number.

There was also an increase in “childhood mortality” records (children aged 0 to 5 years), which jumped from 591 in 2018 to 825 in 2019. The number of records in Amazonas (248 cases), Roraima (133 cases), and Mato Grosso (100 cases) is alarming. As with murder data, SESAI’s information on records relating to suicide and childhood mortality is partial and subject to updates. In other words, these data may be even worse.

Records in the other categories of this chapter in 2019 were: general lack of assistance (65); lack of assistance in indigenous school education (66); lack of health assistance in (85); dissemination of alcoholic beverages and other drugs (20); and death due to lack of health care (31).

Deepening the analysis

This edition of the CIMI Report, which brings the 2019 data, also features articles on specific topics that lead to the understanding of this complex and violent reality faced by indigenous people across Brazil, whether in cities or the demarcated or claimed territories. Among the topics, there are: slash and burn in indigenous lands; the importance of the judgment carried out by the Inter-American Court on the case of the Xukuru Indigenous People; the incarcerated indigenous population in Brazil; a budget analysis of indigenous policy; analysis of suicide among indigenous peoples; the current threats to free or isolated indigenous peoples; and, finally, an analysis of the use, by the current government, of concepts that have already been overcome to restrict indigenous rights.

Caci: 1,193 murders mapped

The Caci platform, a digital map that gathers information on the murders of indigenous people in Brazil, has been updated with the data systematized by this report, Violence against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil. The word Caci means “pain” in Guarani and also serves as an acronym for Cartography of Attacks Against Indigenous People in Portuguese. With the inclusion of data from 2019, the platform now includes georeferenced information on 1,193 murders of indigenous people, gathering cases compiled since 1985.

Errata: on October 9, 2020, two updates were made to this Executive Summary: 1. The total number of “attempted murder” cases went from 24 to 25; and 2. The total number of cases of violence against indigenous people increased from 276 to 277.