The place where we can be who we are

“Land and Territory” mark second day of the Third Continental Meeting

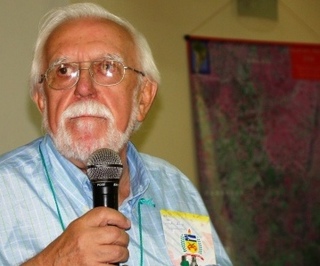

The second day of the Third Continental Meeting of the Guarani People, held in

The second day of the Third Continental Meeting of the Guarani People, held in

Before Meliá could start, the Argentine and Bolivian delegations presented prayers and rituals of welcome, greeting the relatives that arrived during the night at the meeting in the Metropolitan Seminary.

Mix up

Melia, who is a researcher at the Center for Paraguayan Studies Antonio Guasch and at the Institute for Philosophical and Humanistic Studies, started explaining briefly the difference for the Guarani between the terms of “land” and “territory”, which many people mix up. Territory is a much broader term than land, an area that includes notions like planting, animal raising, building your house. Territory is what the Guarani call their Tekohá, which, in its broader meaning means “the place where we can be who we are”.

Where we are a culture

Where we are a culture

This explains why “land” is not the same, and, in fact, only a basic condition for a territory: without it there is no territory, Wihout their land, the Guarani can not live their traditions and not build their history. “They have a very important concept, the concept of teko, the village, which means “where we are cultures”. Hence the importance of the Guarani territory, which has to have all necessary geographic element – a untouched forests, clean water, streams and springs, where they can go fishing, hunting, trapping, and especially plant.

“In several countries the Guarani actually have large stretches land, even big towns, but nonetheless these do not always constitute a territory. In many areas there isn’t even a piece of wood, firewood for cooking. Not to mention forest for hunting, streams for fishing. How are the Guarani to live their traditions, rituals and celebrations without their tekohás? That’s the big difference between land and territory.”

Memory – army in the struggle

Meliá points out the importance of memory and oral history for the struggle of the Guarani people for the demarcation of their ancestral lans. “There exists no tekohá and not even history without memory. If a people has no memory, they do not remember who they are making it very difficult to fight. In court, at the moment that demarcation is at stake, it is necessary to have historical arguments, it is necessary to show that they are Guarani.”

Why does one demarcate land? Because land is a traditional habit of the Guarani people, who live an ecology of the tekohá, a way of live of the place where they can be Guarani.”

The memory of the future

Among virtually all indigenous peoples, oral tradition is very important. It is through the stories – from the elder to the younger – that is told to which people and to which history one belongs. It is essential for the day-to-day struggles that the knowledge and traditions are passed down from generation to generation, that they remain alive and strong among the indigenous.

“That memory is the memory of the past and also of the future, it is like the root that lies beneath the earth and causes the tree to bear fruit, give flowers. The development and expansion of this memory is the future of the people, it is in there that they can find the root of their history, but also the growth of their problems.”

Major changes

Bartomeu Meliá points out three major changes in the recent history of the Guarani people. These changes began with the arrival of the “other”, the non-Guarani, who occupied their territory over the last 50 years. The non-indigenous started to substitute the indigenous people who lived there. “Today you’re here, tomorrow you are not anymore, because these people want to build a city. So the first big change is the replacement of populations and of course with it the arrival of new cities.”

The second major change occurs in the field of economics. If before the Guarani lived primarily from agriculture and the system of reciprocity (exchange of goods), with the creation of new towns and the arrival of companies, they start to become cheap wage laborers. Apart from this, it is important to mention that nature, from which they used to receive their food – fishing, hunting and subsistence farming – is now seen as na important source of wealth. “It’s a very different vision: the logging, the monoculture plantations.”

The last change is also related to the economy, but specifically to distribution system. There is no more reciprocity, exchange and gratuity (in the sense of doing things without expecting something in return). Now, according Meliá, a system of revenge prevails. “you took from me, so I’ll take from you. I give you my labour, If you give me salary.”

In this economy, of maximizing profit and capital accumulation, there is little room subsistence and family farming. In

Just help

After his exposition, several participants raised questions. Like Faride Mariano de Lima, chief of the Kaiowá community Ñanderu Laranjeira, in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul (Brasil). He asked what an anthropologist could do to speed up the demarcation of the traditional land of his people, who live encamped in tarp tents on the brink of the BR 63 state highway.

Although not being an anthropologist, as Meliá stressed, he explained that the role of this professional is important for the accumulation of documents, reports and historical arguments to prepare the demarcation process. “The anthropologist contributes with the documental material. However, it is crucial to point out one thing: the demarcation struggle is not the struggle of the anthropologist. They, as well as others, can help in this struggle. But it is the struggle of the Guarani Kaiowá!”

Cultural night

Cultural night

At the end of the day the participants gathered in groups to discuss issues related to the conference. The meetings were held among the participants of each delegation and the discussions were reported in the plenary that took place earlier in the evening. The day ended with feast and celebration, organized by the Argentine Guarani delegation.